This article is about tides in the Earth's oceans and seas. For other uses, see Tide (disambiguation).

"Tidal", "High tide", and "High water" redirect here. For other uses, see Tidal (disambiguation), High tide (disambiguation), and High water (disambiguation).

|  | |

High tide, Alma, New Brunswick in the Bay of Fundy

|

Low tide at the same fishing port in Bay of Fundy

|

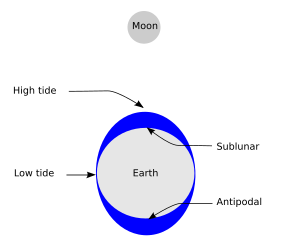

Schematic of the lunar portion of earth's tides showing (exaggerated) high tides at the sublunar and antipodal points for the hypothetical case of an ocean of constant depth with no land. There would also be smaller, superimposed bulges on the sides facing toward and away from the sun.

In Maine (U.S.) low tide occurs roughly at moonrise and high tide with a high moon, corresponding to the simple gravity model of two tidal bulges; at most places however, moon and tides have a phase shift.

Some shorelines experience two almost equal high tides and two low tides each day, called a semi-diurnal tide. Some locations experience only one high and one low tide each day, called a diurnal tide. Some locations experience two uneven tides a day, or sometimes one high and one low each day; this is called a mixed tide. The times and amplitude of the tides at a locale are influenced by the alignment of the Sun and Moon, by the pattern of tides in the deep ocean, by the amphidromic systems of the oceans, and by the shape of the coastline and near-shore bathymetry (see Timing).[1][2][3]

Tides vary on timescales ranging from hours to years due to numerous influences. To make accurate records, tide gauges at fixed stations measure the water level over time. Gauges ignore variations caused by waves with periods shorter than minutes. These data are compared to the reference (or datum) level usually called mean sea level.[4]

While tides are usually the largest source of short-term sea-level fluctuations, sea levels are also subject to forces such as wind and barometric pressure changes, resulting in storm surges, especially in shallow seas and near coasts.

Tidal phenomena are not limited to the oceans, but can occur in other systems whenever a gravitational field that varies in time and space is present. For example, the solid part of the Earth is affected by tides, though this is not as easily seen as the water tidal movements.

Contents[hide] |

[edit] Characteristics

Tide changes proceed via the following stages:- Sea level rises over several hours, covering the intertidal zone; flood tide.

- The water rises to its highest level, reaching high tide.

- Sea level falls over several hours, revealing the intertidal zone; ebb tide.

- The water stops falling, reaching low tide.

Tides are most commonly semi-diurnal (two high waters and two low waters each day), or diurnal (one tidal cycle per day). The two high waters on a given day are typically not the same height (the daily inequality); these are the higher high water and the lower high water in tide tables. Similarly, the two low waters each day are the higher low water and the lower low water. The daily inequality is not consistent and is generally small when the Moon is over the equator.[6]

[edit] Tidal constituents

See also: Earth tide#Tidal constituents

Tidal changes are the net result of multiple influences that act over varying periods. These influences are called tidal constituents. The primary constituents are the Earth's rotation, the positions of the Moon and the Sun relative to Earth, the Moon's altitude (elevation) above the Earth's equator, and bathymetry.Variations with periods of less than half a day are called harmonic constituents. Conversely, cycles of days, months, or years are referred to as long period constituents.

The tidal forces affect the entire earth, but the movement of the solid Earth is only centimeters. The atmosphere is much more fluid and compressible so its surface moves kilometers, in the sense of the contour level of a particular low pressure in the outer atmosphere.

[edit] Principal lunar semi-diurnal constituent

In most locations, the largest constituent is the "principal lunar semi-diurnal", also known as the M2 (or M2) tidal constituent. Its period is about 12 hours and 25.2 minutes, exactly half a tidal lunar day, which is the average time separating one lunar zenith from the next, and thus is the time required for the Earth to rotate once relative to the Moon. Simple tide clocks track this constituent. The lunar day is longer than the Earth day because the Moon orbits in the same direction the Earth spins. This is analogous to the minute hand on a watch crossing the hour hand at 12:00 and then again at about 1:05½ (not at 1:00).The Moon orbits the Earth in the same direction as the Earth rotates on its axis, so it takes slightly more than a day—about 24 hours and 50 minutes—for the Moon to return to the same location in the sky. During this time, it has passed overhead (culmination) once and underfoot once (at an hour angle of 00:00 and 12:00 respectively), so in many places the period of strongest tidal forcing is the above mentioned, about 12 hours and 25 minutes. The moment of highest tide is not necessarily when the Moon is nearest to zenith or nadir, but the period of the forcing still determines the time between high tides.

Because the gravitational field created by the Moon weakens with distance from the Moon, it exerts a slightly stronger than average force on the side of the Earth facing the Moon, and a slightly weaker force on the opposite side. The Moon thus tends to "stretch" the Earth slightly along the line connecting the two bodies. The solid Earth deforms a bit, but ocean water, being fluid, is free to move much more in response to the tidal force, particularly horizontally. As the Earth rotates, the magnitude and direction of the tidal force at any particular point on the Earth's surface change constantly; although the ocean never reaches equilibrium—there is never time for the fluid to "catch up" to the state it would eventually reach if the tidal force were constant—the changing tidal force nonetheless causes rhythmic changes in sea surface height.

[edit] Semi-diurnal range differences

When there are two high tides each day with different heights (and two low tides also of different heights), the pattern is called a mixed semi-diurnal tide.[7][edit] Range variation: springs and neaps

The semi-diurnal range (the difference in height between high and low waters over about half a day) varies in a two-week cycle. Approximately twice a month, around new moon and full moon when the Sun, Moon and Earth form a line (a condition known as syzygy[8]) the tidal force due to the sun reinforces that due to the Moon. The tide's range is then at its maximum: this is called the spring tide, or just springs. It is not named after the season but, like that word, derives from the meaning "jump, burst forth, rise", as in a natural spring.When the Moon is at first quarter or third quarter, the sun and Moon are separated by 90° when viewed from the Earth, and the solar tidal force partially cancels the Moon's. At these points in the lunar cycle, the tide's range is at its minimum: this is called the neap tide, or neaps (a word of uncertain origin).

Spring tides result in high waters that are higher than average, low waters that are lower than average, 'slack water' time that is shorter than average and stronger tidal currents than average. Neaps result in less extreme tidal conditions. There is about a seven-day interval between springs and neaps.

[edit] Lunar altitude

Negative low tide at Ocean Beach in San Francisco

[edit] Bathymetry

The shape of the shoreline and the ocean floor changes the way that tides propagate, so there is no simple, general rule that predicts the time of high water from the Moon's position in the sky. Coastal characteristics such as underwater bathymetry and coastline shape mean that individual location characteristics affect tide forecasting; actual high water time and height may differ from model predictions due to the coastal morphology's effects on tidal flow. However, for a given location the relationship between lunar altitude and the time of high or low tide (the lunitidal interval) is relatively constant and predictable, as is the time of high or low tide relative to other points on the same coast. For example, the high tide at Norfolk, Virginia, predictably occurs approximately two and a half hours before the Moon passes directly overhead.Land masses and ocean basins act as barriers against water moving freely around the globe, and their varied shapes and sizes affect the size of tidal frequencies. As a result, tidal patterns vary. For example, in the U.S., the East coast has predominantly semi-diurnal tides, as do Europe's Atlantic coasts, while the West coast predominantly has mixed tides.[11][12][13]

[edit] Other constituents

These include solar gravitational effects, the obliquity (tilt) of the Earth's equator and rotational axis, the inclination of the plane of the lunar orbit and the elliptical shape of the Earth's orbit of the sun.A compound tide (or overtide) results from the shallow-water interaction of its two parent waves.[14]

[edit] Phase and amplitude

The M2 tidal constituent. Amplitude is indicated by color, and the white lines are cotidal differing by 1 hour. The curved arcs around the amphidromic points show the direction of the tides, each indicating a synchronized 6-hour period.[15][16]

For an ocean in the shape of a circular basin enclosed by a coastline, the cotidal lines point radially inward and must eventually meet at a common point, the amphidromic point. The amphidromic point is at once cotidal with high and low waters, which is satisfied by zero tidal motion. (The rare exception occurs when the tide encircles an island, as it does around New Zealand, Iceland and Madagascar.) Tidal motion generally lessens moving away from continental coasts, so that crossing the cotidal lines are contours of constant amplitude (half the distance between high and low water) which decrease to zero at the amphidromic point. For a semi-diurnal tide the amphidromic point can be thought of roughly like the center of a clock face, with the hour hand pointing in the direction of the high water cotidal line, which is directly opposite the low water cotidal line. High water rotates about the amphidromic point once every 12 hours in the direction of rising cotidal lines, and away from ebbing cotidal lines. This rotation is generally clockwise in the southern hemisphere and counterclockwise in the northern hemisphere, and is caused by the Coriolis effect. The difference of cotidal phase from the phase of a reference tide is the epoch. The reference tide is the hypothetical constituent equilibrium tide on a landless Earth measured at 0° longitude, the Greenwich meridian.

In the North Atlantic, because the cotidal lines circulate counterclockwise around the amphidromic point, the high tide passes New York Harbor approximately an hour ahead of Norfolk Harbor. South of Cape Hatteras the tidal forces are more complex, and cannot be predicted reliably based on the North Atlantic cotidal lines.

[edit] Physics

See also: Tidal force and Theory of tides

[edit] History of tidal physics

Investigation into tidal physics was important in the early development of heliocentrism[citation needed] and celestial mechanics, with the existence of two daily tides being explained by the Moon's gravity. Later the daily tides were explained more precisely by the interaction of the Moon's and the sun's gravity.Galileo Galilei in his 1632 Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems, whose working title was Dialogue on the Tides, gave an explanation of the tides. The resulting theory, however, was incorrect as he attributed the tides to the sloshing of water caused by the Earth's movement around the sun. He hoped to provide mechanical proof of the Earth's movement – the value of his tidal theory is disputed. At the same time Johannes Kepler correctly suggested that the Moon caused the tides, which he based upon ancient observations and correlations, an explanation which was rejected by Galileo. It was originally mentioned in Ptolemy's Tetrabiblos as having derived from ancient observation.

Isaac Newton (1642–1727) was the first person to explain tides as the product of the gravitational attraction of astronomical masses. His explanation of the tides (and many other phenomena) was published in the Principia (1687).[17][18] and used his theory of universal gravitation to explain the lunar and solar attractions as the origin of the tide-generating forces.[19] Newton and others before Pierre-Simon Laplace worked the problem from the perspective of a static system (equilibrium theory), that provided an approximation that described the tides that would occur in a non-inertial ocean evenly covering the whole Earth.[17] The tide-generating force (or its corresponding potential) is still relevant to tidal theory, but as an intermediate quantity (forcing function) rather than as a final result; theory must also consider the Earth's accumulated dynamic tidal response to the applied forces, which response is influenced by bathymetry, Earth's rotation, and other factors.[20]

In 1740, the Académie Royale des Sciences in Paris offered a prize for the best theoretical essay on tides. Daniel Bernoulli, Leonhard Euler, Colin Maclaurin and Antoine Cavalleri shared the prize.

Maclaurin used Newton’s theory to show that a smooth sphere covered by a sufficiently deep ocean under the tidal force of a single deforming body is a prolate spheroid (essentially a three dimensional oval) with major axis directed toward the deforming body. Maclaurin was the first to write about the Earth's rotational effects on motion. Euler realized that the tidal force's horizontal component (more than the vertical) drives the tide. In 1744 Jean le Rond d'Alembert studied tidal equations for the atmosphere which did not include rotation.

Pierre-Simon Laplace formulated a system of partial differential equations relating the ocean's horizontal flow to its surface height, the first major dynamic theory for water tides. The Laplace tidal equations are still in use today. William Thomson, 1st Baron Kelvin, rewrote Laplace's equations in terms of vorticity which allowed for solutions describing tidally driven coastally trapped waves, known as Kelvin waves.[21][22][23]

Others including Kelvin and Henri Poincaré further developed Laplace's theory. Based on these developments and the lunar theory of E W Brown describing the motions of the Moon, Arthur Thomas Doodson developed and published in 1921[24] the first modern development of the tide-generating potential in harmonic form: Doodson distinguished 388 tidal frequencies.[25] Some of his methods remain in use.[26]

[edit] Forces

The tidal force produced by a massive object (Moon, hereafter) on a small particle located on or in an extensive body (Earth, hereafter) is the vector difference between the gravitational force exerted by the Moon on the particle, and the gravitational force that would be exerted on the particle if it were located at the Earth's center of mass. Thus, the tidal force depends not on the strength of the lunar gravitational field, but on its gradient (which falls off approximately as the inverse cube of the distance to the originating gravitational body).[27][28] The solar gravitational force on the Earth is on average 179 times stronger than the lunar, but because the sun is on average 389 times farther from the Earth, its field gradient is weaker. The solar tidal force is 46% as large as the lunar.[29] More precisely, the lunar tidal acceleration (along the Moon-Earth axis, at the Earth's surface) is about 1.1 × 10−7 g, while the solar tidal acceleration (along the Sun-Earth axis, at the Earth's surface) is about 0.52 × 10−7 g, where g is the gravitational acceleration at the Earth's surface.[30] Venus has the largest effect of the other planets, at 0.000113 times the solar effect.

The lunar gravity differential field at the Earth's surface is known as the tide-generating force. This is the primary mechanism that drives tidal action and explains two equipotential tidal bulges, accounting for two daily high waters.

[edit] Laplace's tidal equations

Ocean depths are much smaller than their horizontal extent. Thus, the response to tidal forcing can be modelled using the Laplace tidal equations which incorporate the following features:- The vertical (or radial) velocity is negligible, and there is no vertical shear—this is a sheet flow.

- The forcing is only horizontal (tangential).

- The Coriolis effect appears as an inertial force (fictitious) acting laterally to the direction of flow and proportional to velocity.

- The surface height's rate of change is proportional to the negative divergence of velocity multiplied by the depth. As the horizontal velocity stretches or compresses the ocean as a sheet, the volume thins or thickens, respectively.

The Coriolis effect (inertial force) steers currents moving towards the equator to the west and toward the east for flows moving away from the equator, allowing coastally trapped waves. Finally, a dissipation term can be added which is an analog to viscosity.

[edit] Amplitude and cycle time

The theoretical amplitude of oceanic tides caused by the moon is about 54 centimetres (21 in) at the highest point, which corresponds to the amplitude that would be reached if the ocean possessed a uniform depth, there were no landmasses, and the Earth were rotating in step with the moon's orbit. The sun similarly causes tides, of which the theoretical amplitude is about 25 centimetres (9.8 in) (46% of that of the moon) with a cycle time of 12 hours. At spring tide the two effects add to each other to a theoretical level of 79 centimetres (31 in), while at neap tide the theoretical level is reduced to 29 centimetres (11 in). Since the orbits of the Earth about the sun, and the moon about the Earth, are elliptical, tidal amplitudes change somewhat as a result of the varying Earth–sun and Earth–moon distances. This causes a variation in the tidal force and theoretical amplitude of about ±18% for the moon and ±5% for the sun. If both the sun and moon were at their closest positions and aligned at new moon, the theoretical amplitude would reach 93 centimetres (37 in).Real amplitudes differ considerably, not only because of depth variations and continental obstacles, but also because wave propagation across the ocean has a natural period of the same order of magnitude as the rotation period: if there were no land masses, it would take about 30 hours for a long wavelength surface wave to propagate along the equator halfway around the Earth (by comparison, the Earth's lithosphere has a natural period of about 57 minutes). Earth tides, which raise and lower the bottom of the ocean, and the tide's own gravitational self attraction are both significant and further complicate the ocean's response to tidal forces.

[edit] Dissipation

See also: Tidal acceleration

Earth's tidal oscillations introduce dissipation at an average rate of about 3.75 terawatt.[31] About 98% of this dissipation is by marine tidal movement.[32] Dissipation arises as basin-scale tidal flows drive smaller-scale flows which experience turbulent dissipation. This tidal drag creates torque on the moon that gradually transfers angular momentum to its orbit, and a gradual increase in Earth–moon separation. The equal and opposite torque on the Earth correspondingly decreases its rotational velocity. Thus, over geologic time, the moon recedes from the Earth, at about 3.8 centimetres (1.5 in)/year, lengthening the terrestrial day.[33] Day length has increased by about 2 hours in the last 600 million years. Assuming (as a crude approximation) that the deceleration rate has been constant, this would imply that 70 million years ago, day length was on the order of 1% shorter with about 4 more days per year.[edit] Observation and prediction

[edit] History

Brouscon's Almanach of 1546: Compass bearings of high waters in the Bay of Biscay (left) and the coast from Brittany to Dover (right).

In the 2nd century BC, the Babylonian astronomer, Seleucus of Seleucia, correctly described the phenomenon of tides in order to support his heliocentric theory.[34] He correctly theorized that tides were caused by the moon, although he believed that the interaction was mediated by the pneuma. He noted that tides varied in time and strength in different parts of the world. According to Strabo (1.1.9), Seleucus was the first to link tides to the lunar attraction, and that the height of the tides depends on the moon's position relative to the sun.[35]

The Naturalis Historia of Pliny the Elder collates many tidal observations, e.g., the spring tides are a few days after (or before) new and full moon and are highest around the equinoxes, though Pliny noted many relationships now regarded as fanciful. In his Geography, Strabo described tides in the Persian Gulf having their greatest range when the moon was furthest from the plane of the equator. All this despite the relatively small amplitude of Mediterranean basin tides. (The strong currents through the Euripus Strait and the Strait of Messina puzzled Aristotle.) Philostratus discussed tides in Book Five of The Life of Apollonius of Tyana. Philostratus mentions the moon, but attributes tides to "spirits". In Europe around 730 AD, the Venerable Bede described how the rising tide on one coast of the British Isles coincided with the fall on the other and described the time progression of high water along the Northumbrian coast.

The first tide table in China was recorded in 1056 AD primarily for visitors wishing to see the famous tidal bore in the Qiantang River. The first known British tide table is thought to be that of John Wallingford, who died Abbot of St. Albans in 1213, based on high water occurring 48 minutes later each day, and three hours earlier at the Thames mouth than upriver at London.[36]

William Thomson (Lord Kelvin) led the first systematic harmonic analysis of tidal records starting in 1867. The main result was the building of a tide-predicting machine using a system of pulleys to add together six harmonic time functions. It was "programmed" by resetting gears and chains to adjust phasing and amplitudes. Similar machines were used until the 1960s.[37]

The first known sea-level record of an entire spring–neap cycle was made in 1831 on the Navy Dock in the Thames Estuary. Many large ports had automatic tide gage stations by 1850.

William Whewell first mapped co-tidal lines ending with a nearly global chart in 1836. In order to make these maps consistent, he hypothesized the existence of amphidromes where co-tidal lines meet in the mid-ocean. These points of no tide were confirmed by measurement in 1840 by Captain Hewett, RN, from careful soundings in the North Sea.[21]

[edit] Timing

The local bathymetry greatly influences the tide's exact time and height at a particular coastal point. There are some extreme cases: the Bay of Fundy, on the east coast of Canada, features the world's largest well-documented tidal ranges, 17 metres (56 ft) because of its shape.[40] Some experts[who?] believe Ungava Bay in northern Quebec to have even higher tidal ranges,[citation needed] but it is free of pack ice for only about four months every year, while the Bay of Fundy rarely freezes.

Southampton in the United Kingdom has a double high water caused by the interaction between the region's different tidal harmonics, caused primarily by the east/west orientation of the English Channel and the fact that when it is high water at Dover it is low water at Land's End (some 300 nautical miles distant) and vice versa. This is contrary to the popular belief that the flow of water around the Isle of Wight creates two high waters. The Isle of Wight is important, however, since it is responsible for the 'Young Flood Stand', which describes the pause of the incoming tide about three hours after low water.[41]

Because the oscillation modes of the Mediterranean Sea and the Baltic Sea do not coincide with any significant astronomical forcing period, the largest tides are close to their narrow connections with the Atlantic Ocean. Extremely small tides also occur for the same reason in the Gulf of Mexico and Sea of Japan. Elsewhere, as along the southern coast of Australia, low tides can be due to the presence of a nearby amphidrome.

[edit] Analysis

Isaac Newton's theory of gravitation first enabled an explanation of why there were generally two tides a day, not one, and offered hope for detailed understanding. Although it may seem that tides could be predicted via a sufficiently detailed knowledge of the instantaneous astronomical forcings, the actual tide at a given location is determined by astronomical forces accumulated over many days. Precise results require detailed knowledge of the shape of all the ocean basins—their bathymetry and coastline shape.Current procedure for analysing tides follows the method of harmonic analysis introduced in the 1860s by William Thomson. It is based on the principle that the astronomical theories of the motions of sun and moon determine a large number of component frequencies, and at each frequency there is a component of force tending to produce tidal motion, but that at each place of interest on the Earth, the tides respond at each frequency with an amplitude and phase peculiar to that locality. At each place of interest, the tide heights are therefore measured for a period of time sufficiently long (usually more than a year in the case of a new port not previously studied) to enable the response at each significant tide-generating frequency to be distinguished by analysis, and to extract the tidal constants for a sufficient number of the strongest known components of the astronomical tidal forces to enable practical tide prediction. The tide heights are expected to follow the tidal force, with a constant amplitude and phase delay for each component. Because astronomical frequencies and phases can be calculated with certainty, the tide height at other times can then be predicted once the response to the harmonic components of the astronomical tide-generating forces has been found.

The main patterns in the tides are

- the twice-daily variation

- the difference between the first and second tide of a day

- the spring–neap cycle

- the annual variation

When confronted by a periodically varying function, the standard approach is to employ Fourier series, a form of analysis that uses sinusoidal functions as a basis set, having frequencies that are zero, one, two, three, etc. times the frequency of a particular fundamental cycle. These multiples are called harmonics of the fundamental frequency, and the process is termed harmonic analysis. If the basis set of sinusoidal functions suit the behaviour being modelled, relatively few harmonic terms need to be added. Orbital paths are very nearly circular, so sinusoidal variations are suitable for tides.

For the analysis of tide heights, the Fourier series approach has in practice to be made more elaborate than the use of a single frequency and its harmonics. The tidal patterns are decomposed into many sinusoids having many fundamental frequencies, corresponding (as in the lunar theory) to many different combinations of the motions of the Earth, the moon, and the angles that define the shape and location of their orbits.

For tides, then, harmonic analysis is not limited to harmonics of a single frequency.[42] In other words, the harmonies are multiples of many fundamental frequencies, not just of the fundamental frequency of the simpler Fourier series approach. Their representation as a Fourier series having only one fundamental frequency and its (integer) multiples would require many terms, and would be severely limited in the time-range for which it would be valid.

The study of tide height by harmonic analysis was begun by Laplace, William Thomson (Lord Kelvin), and George Darwin. A.T. Doodson extended their work, introducing the Doodson Number notation to organise the hundreds of resulting terms. This approach has been the international standard ever since, and the complications arise as follows: the tide-raising force is notionally given by sums of several terms. Each term is of the form

- A·cos(w·t + p)

- A(t) = A·(1 + Aa·cos(wa·t + pa)) ,

- A·[1 + Aa·cos(wa ·t + pa)]·cos(w·t + p)

- cos(x)·cos(y) = ½·cos( x + y ) + ½·cos( x–y ) ,

Remember that astronomical tides do not include weather effects. Also, changes to local conditions (sandbank movement, dredging harbour mouths, etc.) away from those prevailing at the measurement time affect the tide's actual timing and magnitude. Organisations quoting a "highest astronomical tide" for some location may exaggerate the figure as a safety factor against analytical uncertainties, distance from the nearest measurement point, changes since the last observation time, ground subsidence, etc., to avert liability should an engineering work be overtopped. Special care is needed when assessing the size of a "weather surge" by subtracting the astronomical tide from the observed tide.

Careful Fourier data analysis over a nineteen-year period (the National Tidal Datum Epoch in the U.S.) uses frequencies called the tidal harmonic constituents. Nineteen years is preferred because the Earth, moon and sun's relative positions repeat almost exactly in the Metonic cycle of 19 years, which is long enough to include the 18.613 year lunar nodal tidal constituent. This analysis can be done using only the knowledge of the forcing period, but without detailed understanding of the mathematical derivation, which means that useful tidal tables have been constructed for centuries.[43] The resulting amplitudes and phases can then be used to predict the expected tides. These are usually dominated by the constituents near 12 hours (the semi-diurnal constituents), but there are major constituents near 24 hours (diurnal) as well. Longer term constituents are 14 day or fortnightly, monthly, and semiannual. Semi-diurnal tides dominated coastline, but some areas such as the South China Sea and the Gulf of Mexico are primarily diurnal. In the semi-diurnal areas, the primary constituents M2 (lunar) and S2 (solar) periods differ slightly, so that the relative phases, and thus the amplitude of the combined tide, change fortnightly (14 day period).[44]

In the M2 plot above, each cotidal line differs by one hour from its neighbors, and the thicker lines show tides in phase with equilibrium at Greenwich. The lines rotate around the amphidromic points counterclockwise in the northern hemisphere so that from Baja California Peninsula to Alaska and from France to Ireland the M2 tide propagates northward. In the southern hemisphere this direction is clockwise. On the other hand M2 tide propagates counterclockwise around New Zealand, but this is because the islands act as a dam and permit the tides to have different heights on the islands' opposite sides. (The tides do propagate northward on the east side and southward on the west coast, as predicted by theory.)

The exception is at Cook Strait where the tidal currents periodically link high to low water. This is because cotidal lines 180° around the amphidromes are in opposite phase, for example high water across from low water at each end of Cook Strait. Each tidal constituent has a different pattern of amplitudes, phases, and amphidromic points, so the M2 patterns cannot be used for other tide components.

[edit] Example calculation

Further information: The article on A.T. Doodson has a fully worked example calculation for Bridgeport, Connecticut, U.S.A.

When the Earth, moon, and sun are in line (sun–Earth–moon, or sun–moon–Earth) the two main influences combine to produce spring tides; when the two forces are opposing each other as when the angle moon–Earth–sun is close to ninety degrees, neap tides result. As the moon moves around its orbit it changes from north of the equator to south of the equator. The alternation in high tide heights becomes smaller, until they are the same (at the lunar equinox, the moon is above the equator), then redevelop but with the other polarity, waxing to a maximum difference and then waning again.

[edit] Current

The tides' influence on current flow is much more difficult to analyse, and data is much more difficult to collect. A tidal height is a simple number which applies to a wide region simultaneously. A flow has both a magnitude and a direction, both of which can vary substantially with depth and over short distances due to local bathymetry. Also, although a water channel's center is the most useful measuring site, mariners object when current-measuring equipment obstructs waterways. A flow proceeding up a curved channel is the same flow, even though its direction varies continuously along the channel. Surprisingly, flood and ebb flows are often not in opposite directions. Flow direction is determined by the upstream channel's shape, not the downstream channel's shape. Likewise, eddies may form in only one flow direction.Nevertheless, current analysis is similar to tidal analysis: in the simple case, at a given location the flood flow is in mostly one direction, and the ebb flow in another direction. Flood velocities are given positive sign, and ebb velocities negative sign. Analysis proceeds as though these are tide heights.

In more complex situations, the main ebb and flood flows do not dominate. Instead, the flow direction and magnitude trace an ellipse over a tidal cycle (on a polar plot) instead of along the ebb and flood lines. In this case, analysis might proceed along pairs of directions, with the primary and secondary directions at right angles. An alternative is to treat the tidal flows as complex numbers, as each value has both a magnitude and a direction.

Tide flow information is most commonly seen on nautical charts, presented as a table of flow speeds and bearings at hourly intervals, with separate tables for spring and neap tides. The timing is relative to high water at some harbour where the tidal behaviour is similar in pattern, though it may be far away.

As with tide height predictions, tide flow predictions based only on astronomical factors do not incorporate weather conditions, which can completely change the outcome.

The tidal flow through Cook Strait between the two main islands of New Zealand is particularly interesting, as the tides on each side of the strait are almost exactly out of phase, so that one side's high water is simultaneous with the other's low water. Strong currents result, with almost zero tidal height change in the strait's center. Yet, although the tidal surge normally flows in one direction for six hours and in the reverse direction for six hours, a particular surge might last eight or ten hours with the reverse surge enfeebled. In especially boisterous weather conditions, the reverse surge might be entirely overcome so that the flow continues in the same direction through three or more surge periods.

A further complication for Cook Strait's flow pattern is that the tide at the north side (e.g. at Nelson) follows the common bi-weekly spring–neap tide cycle (as found along the west side of the country), but the south side's tidal pattern has only one cycle per month, as on the east side: Wellington, and Napier.

The graph of Cook Strait's tides shows separately the high water and low water height and time, through November 2007; these are not measured values but instead are calculated from tidal parameters derived from years-old measurements. Cook Strait's nautical chart offers tidal current information. For instance the January 1979 edition for 41°13·9’S 174°29·6’E (north west of Cape Terawhiti) refers timings to Westport while the January 2004 issue refers to Wellington. Near Cape Terawhiti in the middle of Cook Strait the tidal height variation is almost nil while the tidal current reaches its maximum, especially near the notorious Karori Rip. Aside from weather effects, the actual currents through Cook Strait are influenced by the tidal height differences between the two ends of the strait and as can be seen, only one of the two spring tides at the north end (Nelson) has a counterpart spring tide at the south end (Wellington), so the resulting behaviour follows neither reference harbour.[citation needed]

[edit] Power generation

Main article: Tidal power

Tidal energy can be extracted by two means: inserting a water turbine into a tidal current, or building ponds that release/admit water through a turbine. In the first case, the energy amount is entirely determined by the timing and tidal current magnitude. However, the best currents may be unavailable because the turbines would obstruct ships. In the second, the impoundment dams are expensive to construct, natural water cycles are completely disrupted, ship navigation is disrupted. However, with multiple ponds, power can be generated at chosen times. So far, there are few installed systems for tidal power generation (most famously, La Rance by Saint Malo, France) which faces many difficulties. Aside from environmental issues, simply withstanding corrosion and biological fouling pose engineering challenges.Tidal power proponents point out that, unlike wind power systems, generation levels can be reliably predicted, save for weather effects. While some generation is possible for most of the tidal cycle, in practice turbines lose efficiency at lower operating rates. Since the power available from a flow is proportional to the cube of the flow speed, the times during which high power generation is possible are brief.

[edit]

Tidal flows are important for navigation, and significant errors in position occur if they are not accommodated. Tidal heights are also important; for example many rivers and harbours have a shallow "bar" at the entrance which prevents boats with significant draft from entering at low tide.Until the advent of automated navigation, competence in calculating tidal effects was important to naval officers. The certificate of examination for lieutenants in the Royal Navy once declared that the prospective officer was able to "shift his tides".[45]

Tidal flow timings and velocities appear in tide charts or a tidal stream atlas. Tide charts come in sets. Each chart covers a single hour between one high water and another (they ignore the leftover 24 minutes) and show the average tidal flow for that hour. An arrow on the tidal chart indicates the direction and the average flow speed (usually in knots) for spring and neap tides. If a tide chart is not available, most nautical charts have "tidal diamonds" which relate specific points on the chart to a table giving tidal flow direction and speed.

The standard procedure to counteract tidal effects on navigation is to (1) calculate a "dead reckoning" position (or DR) from travel distance and direction, (2) mark the chart (with a vertical cross like a plus sign) and (3) draw a line from the DR in the tide's direction. The distance the tide moves the boat along this line is computed by the tidal speed, and this gives an "estimated position" or EP (traditionally marked with a dot in a triangle).

Tidal Indicator, Delaware River, Delaware c. 1897. At the time shown in the figure, the tide is 1¼ feet above mean low water and is still falling, as indicated by pointing of the arrow. Indicator is powered by system of pulleys, cables and a float. (Report Of The Superintendent Of The Coast & Geodetic Survey Showing The Progress Of The Work During The Fiscal Year Ending With June 1897 (p. 483))

Tide tables list each day's high and low water heights and times. To calculate the actual water depth, add the charted depth to the published tide height. Depth for other times can be derived from tidal curves published for major ports. The rule of twelfths can suffice if an accurate curve is not available. This approximation presumes that the increase in depth in the six hours between low and high water is: first hour — 1/12, second — 2/12, third — 3/12, fourth — 3/12, fifth — 2/12, sixth — 1/12.

[edit] Biological aspects

[edit] Intertidal ecology

Main article: Intertidal ecology

Intertidal ecology is the study of intertidal ecosystems, where organisms live between the low and high water lines. At low water, the intertidal is exposed (or ‘emersed’) whereas at high water, the intertidal is underwater (or ‘immersed’). Intertidal ecologists therefore study the interactions between intertidal organisms and their environment, as well as among the different species. The most important interactions may vary according to the type of intertidal community. The broadest classifications are based on substrates — rocky shore or soft bottom.Intertidal organisms experience a highly variable and often hostile environment, and have adapted to cope with and even exploit these conditions. One easily visible feature is vertical zonation, in which the community divides into distinct horizontal bands of specific species at each elevation above low water. A species' ability to cope with desiccation determines its upper limit, while competition with other species sets its lower limit.

Humans use intertidal regions for food and recreation. Overexploitation can damage intertidals directly. Other anthropogenic actions such as introducing invasive species and climate change have large negative effects. Marine Protected Areas are one option communities can apply to protect these areas and aid scientific research.

[edit] Biological rhythms

The approximately fortnightly tidal cycle has large effects on intertidal[46] and marine organisms.[47] Hence their biological rhythms tend to occur in rough multiples of this period. Many other animals such as the vertebrates, display similar rhythms. Examples include gestation and egg hatching. In humans, the menstrual cycle lasts roughly a lunar month, an even multiple of the tidal period. Such parallels at least hint at the common descent of all animals from a marine ancestor.[48][edit] Other tides

When oscillating tidal currents in the stratified ocean flow over uneven bottom topography, they generate internal waves with tidal frequencies. Such waves are called internal tides.Shallow areas in otherwise open water can experience rotary tidal currents, flowing in directions that continually change and thus the flow direction (not the flow) completes a full rotation in 12½ hours (for example, the Nantucket Shoals).[49]

In addition to oceanic tides, large lakes can experience small tides and even planets can experience atmospheric tides and Earth tides. These are continuum mechanical phenomena. The first two take place in fluids. The third affects the Earth's thin solid crust surrounding its semi-liquid interior (with various modifications).

[edit] Lake tides

Large lakes such as Superior and Erie can experience tides of 1 to 4 cm, but these can be masked by meteorologically induced phenomena such as seiche.[50] The tide in Lake Michigan is described as 0.5 to 1.5 inches (13 to 38 mm)[51] or 1¾ inches.[52][edit] Atmospheric tides

Atmospheric tides are negligible at ground level and aviation altitudes, masked by weather's much more important effects. Atmospheric tides are both gravitational and thermal in origin and are the dominant dynamics from about 80 to 120 kilometres (50 to 75 mi), above which the molecular density becomes too low to support fluid behavior.[edit] Earth tides

Main article: Earth tide

Earth tides or terrestrial tides affect the entire Earth's mass, which acts similarly to a liquid gyroscope with a very thin crust. The Earth's crust shifts (in/out, east/west, north/south) in response to lunar and solar gravitation, ocean tides, and atmospheric loading. While negligible for most human activities, terrestrial tides' semi-diurnal amplitude can reach about 55 centimetres (22 in) at the equator—15 centimetres (5.9 in) due to the sun—which is important in GPS calibration and VLBI measurements. Precise astronomical angular measurements require knowledge of the Earth's rotation rate and nutation, both of which are influenced by Earth tides. The semi-diurnal M2 Earth tides are nearly in phase with the moon with a lag of about two hours.[citation needed]Some particle physics experiments must adjust for terrestrial tides.[53] For instance, at CERN and SLAC, the very large particle accelerators account for terrestrial tides. Among the relevant effects are circumference deformation for circular accelerators and particle beam energy.[54][55] Since tidal forces generate currents in conducting fluids in the Earth's interior, they in turn affect the Earth's magnetic field. Earth tides have also been linked to the triggering of earthquakes[56] (see also earthquake prediction).