That turned out to be a disastrous mistake, one that eventually led to the demise of the group.

Clicking on the link didn’t provide any information. It didn’t even open a blank page. But, with each click, spy software, known as malware, was surreptitiously downloaded onto the computers of each staffer who tried to open the document. That program was designed to steal workers’ files, intercept their emails and snoop on their Skype communications.

According to research by the Electronic Frontier Foundation and Citizen Lab, both activist bodies focused on internet freedom, the malware was likely created by a well-known government supplier called Hacking Team. Hacking Team told BBC Capital it cannot reveal its customers and therefore would never confirm nor deny it created the spyware.

Almiraat strongly believes a government was behind the attack.

“This piece of (malware) software costs half a million dollars. I don't know anybody who considers themselves to be our enemy who has the resources and time to purchase this thing and target our group in this manner,” other than a government, he said. The Moroccan government had not responded to several requests from BBC Capital for comment at the time of publication.

This kind of targeted approach is typical of government-led attacks, said David Emm, senior security researcher at computer security firm, Kaspersky Lab.

“People are susceptible to social engineering tricks for various reasons. Sometimes they simply don't realise the danger,” Emm said.

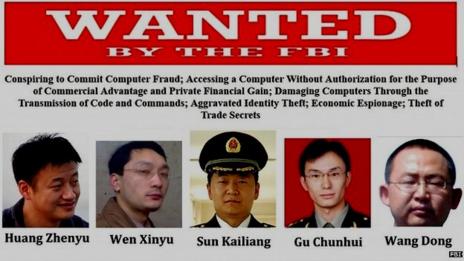

READ MORE: The US has charged five Chinese army officers with hacking into American companies.

Wide-range of targets

Some nations are using such tactics to watch over activists, experts said. But others are increasingly using hackers to acquire intellectual property to support businesses on their own turf, whilst hoping to gather data related to national security (like military secrets), according to Mark Brown, director of information security at business consultancy EY, formerly Ernst & Young.

A broad range of industries fall into the bull’s-eye of such attacks. In February, security firm Kaspersky disclosed a cyber-espionage campaign that affected not just government institutions, but also diplomatic offices and embassies, energy, oil and gas companies, research institutions, private equity firms and activists.

Emails sent to targets contained links to apparently benign websites, promising recipients everything from videos related to political subjects to food recipes, whatever the intended recipient would find interesting enough to open. If the user clicked on the link, their system was infected and the malware could record Skype conversations or take pictures of users’ screens and send the information back to the attackers.

“Nation-state attacks are increasingly focusing on economic growth and competitive advantage as well as national security issues,” said Brown. “Companies of any size can be attacked to gain access to information which can accelerate the economic interests of a nation.”

Devastating impact

The impact on a targeted organisation can vary, but it can be more destructive than even covert surveillance. In 2013, for instance, security company McAfee investigated attacks on South Korean banks.

“Tens of thousands of computers had their hard drives wiped with significant disruption to the cash machine network amongst other systems,” said Raj Samani, chief technology officer for McAfee in Europe, the Middle East and Africa.

South Korea suspected North Korea had used a malware program on the banks, though that country denied any wrongdoing. Whoever was behind the attack caused significant disruption. Customers for Shinhan Bank, for example, were unable to access either internet banking or cash machines for at least two hours. Later in the year, citing figures from the defence ministry’s cyber division, Chung Hee-soo of the ruling Saenuri Party claimed that attacks from North Korea in 2013, which included those on the banks, had cost South Korea 800bn won ($756m) in economic damage.

Even small firms or those with minor interests can be targets — and they’re often most vulnerable because they believe “that their operations are not sensitive enough to attack,” said Brown. “We are increasingly seeing companies further down the supply chain as targets.”

Employees beware

Every developed nation is believed to be involved in carrying out such attacks, and each has experienced digital attempts on their own properties, affecting both private and public organisations, said Jaime Blasco, director of AlienVault Labs, an organisation that researches attacks and provides advice to customers.

“The usual suspects have been always been countries such as Russia, China and with the Snowden revelations [of mass spying by the US National Security Agency] we can include the US,” Blasco said. “That said, it makes perfect sense that most governments around the world have developed these capabilities and are actively using that to support traditional intelligence operations.”

Any employee can be targeted, from the CEO to human resources to the information technology team. But Mikko Hypponen, chief research officer at Finnish security firm F-Secure, says there are a select few who are more likely to attract hackers.

“It's fairly easy to figure out who is the most likely target: board members, chief executives, secretaries and admins,” who have direct lines into the most valuable information on a business’ network, he said.

If workers are duped into letting malware on their company PC, the financial cost to their employer could be severe. A survey of 800 chief information officers by McAfee revealed in March that of those who had been breached by advanced attacks in the last 12 months, the cost to the organisation was upwards of £600,000 ($1m USD).

Preventing cyber hacks

Every department should receive training to reduce the exposure of business assets to attackers, Blasco said. Workers should be taught to identify suspicious emails, he added.

Caution using public wi-fi is vital, as information shared over those networks can be easily intercepted by a hacker, he said. Since social media accounts can also prove valuable to government attackers—and activists in particular have had their Facebook accounts hacked — it’s critical to use strong passwords for such accounts and be careful with what is shared on Facebook, LinkedIn and Twitter, said Emm.

“If you wouldn’t write it in a letter to the local newspaper, don’t post it online,” Emm said.

Anti-virus software, relied on to stop malicious software infecting PCs, is not always very effective at preventing other kinds of attack either.

15 April 2014

When governments attack — online

(Thinkstock)

In mid-2012, Hisham Almiraat and his colleagues at Mamfakinch, a pro-democracy citizen media project, received a curious email.

It appeared to offer information on a scandal involving a Moroccan politician, an enticing story to an online publication that was openly anti-government. The sender said he did not want to be identified, but simply recommended the recipients open the file if they wanted some potentially newsworthy content. Some at the group, who were spread across cities in Morocco, downloaded the purported Microsoft Word document, for which the sender had offered a link.

The Heartbleed bug surfaced earlier this month, after a pernicious flaw was discovered in a widely used web encryption program known as OpenSSL. This glitch may allow attackers to trick machines in to giving up data they should not leak, such as passwords for email accounts. To exploit the weakness, attackers don’t need to use malware which means an anti-virus system may not prevent a leak. The only way to stop this type of attack would be to fix or ‘patch’ the Heartbleed vulnerability, according to experts.

Government attacks can be catastrophic. Mamfakinch, which was given a Breaking Borders Award in 2012 by Google and Global Voices, was rendered all but out of business as a result of the attempt on its systems.

Not long after the attack, the number of people involved in the running of Mamfakinch, from editorial staff to technical employees, dropped from 35 to just five. The group has now shut down indefinitely. Even though the attack was caught and the body does not believe the malware succeeded in its aims to spy on employees, the mere fact that Mamfakinch was targeted was enough to scare off sources who were fearful of arrest and further punishment from the authorities.

“When you are dealing with very sensitive political issues and … you're targeted by software of this kind, that really destroys this trust around protecting anonymity. It created a psychological flaw in our organisation,” Almiraat said. “After that people just couldn’t keep on working with us.”

No comments:

Post a Comment